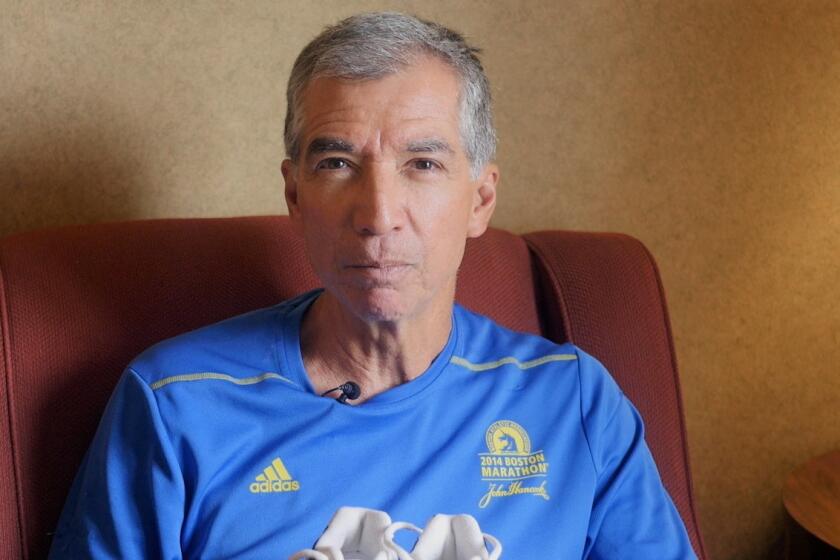

Arts patron Harvey White shares philosophy

Harvey P. White

Born: March 19, 1934 in Rhode Island

Education: Attended West Virginia Wesleyan College; Marshall University, BA in economics

Work Experience: Chairman, (SHW)2 Enterprises since 2004; Founder, CEO Leap Wireless International, 1998-2004; co-founder, director of Qualcomm, 1985, president, 1992-1998; CFO/COO Linkabit Corp., 1978-’85; prior executive positions at Rohr Industries, Raytheon, Whittaker and TRW. On boards of Brain Corp., ViaSat, S.D. Padres.

Family: Wife, Sheryl; three adult children, one stepson, eight grandchildren.

Home: Del Mar

Community involvement: Board member: Old Globe Theatre, S.D. Museum of Art, Salk Institute; UCSD Rady School of Management advisory board and past board member of West Wireless Health Institute.

Philanthropy: Support for opera, symphony, local art museums and theaters. Donated $6 million-plus to Old Globe’s theater-in-the-round, since renamed Sheryl & Harvey White Theatre.

Harvey and Sheryl White are firmly aboard the music and arts bandwagon.

While Harvey, a cofounder of Qualcomm, believes strongly the core subjects of science, technology, engineering and math — or STEM — should become STEAM, with an “A” added for the arts. Sheryl, likewise, is committed to supporting San Diego’s dynamic mix of theater, opera, symphony and art museums.

In fact, the couple met at the Old Globe Theatre in Balboa Park while serving as board members. And, in December, 2001, they married on the Old Globe stage. The backdrop happened to be the set of the “Grinch” but there is nothing Grinch-like about their commitment to San Diego’s future. They give both time and money, operating as team, a concept embodied in their (SHW)2 Enterprises (Sheryl and Harvey White squared) firm. Harvey shared his story with the U-T.

Q: After stepping down from Leap Wireless at age 70, you formed your own business development and consulting firm. Why?

A: When I told Sheryl I was going to retire, she said, “I married you for better or for worse, but not for lunch. Go do something.” So I did.

Q: You’ve called it a terrible shame that our government has decided it’s not important to teach the arts. Why?

A: There’s a good bit of evidence that says, to be innovative, you need to use both sides of your brain. What concerns me is people don’t understand that the marriage of arts and humanities with engineering is an economic issue. It’s not just a nicety. We’re going to win in the economic world by our innovation. Yet the United States has gone from being rated No. 1 to No. 8 in innovation. … But no politicians are going to say, “I want to put money into the arts,” unless you give them a cover, an economic rationale.

Q: How can our schools adapt?

A: The education system in this country is not broken. It’s just 150 years out of date. It was designed by Andrew Carnegie to get farm kids off the farm, teach them now to read and write so they could work in the factories. It worked pretty well until the 1960s, but not today. The idea that you drill students on facts is passé. Schools need to help you find the facts you need, then teach you how to put two or three facts together to see what happens — systems thinking.

Q: Is anyone doing this?

A: In Massachusetts, it’s part of a law they passed a couple of years ago that, for economic development, schools be graded on their creativity. At (San Diego’s) High Tech High, students create something, then write a book telling how they did it. There are similar things going on in Chula Vista and National City schools. The problem is, it’s just individual little programs. There’s no overreaching national priority.

Q: Your parents divorced when you were 2. Your mother, who later remarried, struggled to raise you during the depression. Did that inspire your charitable giving?

A: My mom eventually got a job as a reporter and started tithing, but not to the church. She set aside 10 percent of everything she made for a fund to help people in the neighborhood, say elderly ladies up the street who needed plumbing repairs. That made quite an impression on me.

The first significant philanthropic thing I did was set up two scholarships, one in the high school I (and my mom) graduated from in West Virginia, then another one in my stepfather’s school in Portsmouth, Ohio.

Q: How was your work ethic forged?

A: We were very poor. When my mother and stepfather married in 1939, they made $14 a week. I carried newspapers when I was 12. I got a work permit at 14. I worked in a warehouse, a drugstore. I had a great job laying electric and was a rod man with a surveying crew. One summer I worked on a riverboat.

Q: Did you have any setbacks en route to success?

A: I always say to people I made three or four really terrible business decisions. If I hadn’t, I wouldn’t be where I am today. I’m a great believer in Yogi Berra’s saying, “When you come to a fork in the road … take it.”

Q: What charitable contribution gives you the most satisfaction?

A: We really feel good about giving money to something and they do a good job with it. Many people I’ve met — directors, producers, actors — have come to town and said the (Harvey and Sheryl White) Theatre is one of the finest theaters they’ve ever been in from an operational standpoint. That’s satisfying.

Q: What is your philosophy of giving?

A: We tend to concentrate on education and the arts. And we like to see them mixed together. We are not single cause driven. We give to different organizations. Most of our giving is back to this community where we made our money. We haven’t made a lot of splashy gifts. We’re not excited about our name being on lots of buildings.

Q: What is your charitable time commitment?

A: A couple of years ago, I was chairing two boards at Salk, involved in the West Wireless Health Institute and on the executive search committee for the San Diego Museum of Art. I was probably spending 30 or 40 percent, maybe half, of my time on these things. I cut back because of some business projects … but I’m ready to get more involved. Sheryl spends a lot of time with the Arts Commission. She’s on the finance committee of the Old Globe and has helped the opera with corporate development. She has put on more galas!

Q: How have you made a difference in someone’s life?

A: I was on a trip with the American Indian College Fund in the Southwest. On the last day, a UCSD professor on the tour came and sat next to me. “I just want to tell you something,” he said. “I’ve got a pension from the university and we live comfortably, but we could never give money like we give to the American Indian College Fund if it wasn’t for the fact that we invested in Qualcomm. We use all the money from that to give back.” That was very touching. There are a lot of closet millionaires in San Diego (because of Qualcomm). I am optimistic they’ll start giving back to the community.

Q: Do you have a motto?

A: (White pointed to a saying on his bookcase): “The best way to predict the future is to create it.” — Peter Drucker.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.