The Groove Issue 47 - How Water Makes Your Ideas Flow

HOW WATER MAKES YOUR IDEAS FLOW

Artists have known this for a long time, as have entrepreneurs and scientists: being close to water stimulates your creativity in ways nothing else does. We have a fundamental evolutionary connection to water. It’s the matrix of life and of our bodies.

For example, Lin-Manuel Miranda attributes the idea of creating Hamilton to being away on a summer holiday on a beach in Mexico and able to read Ron Chernow’s extensive Alexander Hamilton biography. Ernest Hemingway wrote his finest novel, The Old Man and the Sea, in 1951 when he lived in Cayo Blanco, Cuba. That was the work that turned him into a celebrity.

After being burned out by the demands of a corporate job in New York City, entrepreneur Mike Coughlin, moved back with his parents in Cape Cod. While spending time by the ocean every day, he came up with the idea to open his company, The Blue Ocean Life, which helps provide access to surf therapy for people who are mentally, physically or socially disadvantaged.

Of course, being far away from the worries and stresses of daily life helps, but I set out to investigate if there’s something else about being close to water that prompts the mind to make associations or solve problems in new ways. And I found that there is a connection with being close to water that is worth examining.

How Monet’s Obsession with Water Served Him Well

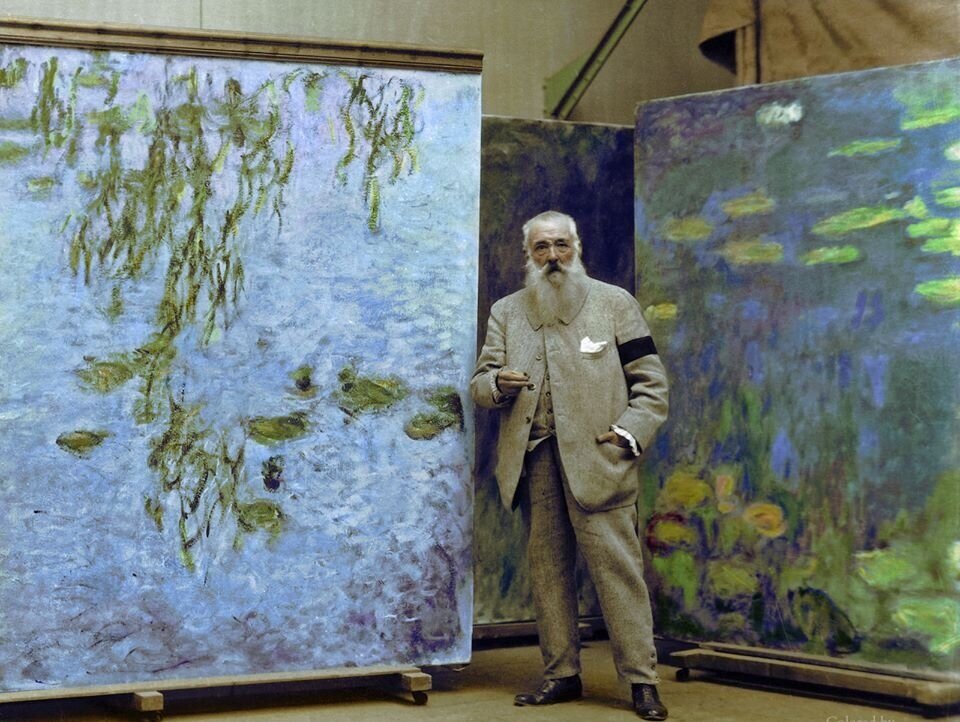

Claude Monet in his studio in 1923 surrounded by his famous Water Lilies paintings. Image re-colored by Dana Keller.

Throughout his life, Claude Monet made a conscious choice to always be close to water. In his prolific career, he created some 2,500 paintings, drawings and pastels. That’s an impressive number for an artist even by today’s standards. Which makes me think that Monet’s proximity to water fueled his creativity quite a bit.

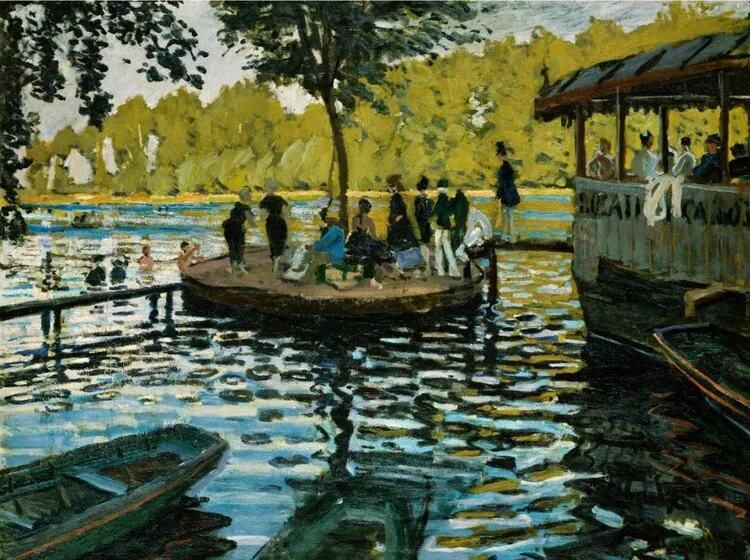

A very large part of his work was dedicated to capturing hundreds of different bodies of water, from the canals of Venice to bathers and a floating restaurant in a French resort called La Grenouillère.

Regarding the Seine, an enormous source of inspiration to him that he constantly physically approached, he said: “I have painted it all my life, at all hours of the day, at all times of the year, from Paris to the sea…Argenteuil, Poissy, Vétheuil, Giverny, Rouen, Le Havre.”

Claude Monet, La Grenouillère, 1869, oil on canvas.

In 1883, Monet moved to a property in Giverny, France. It was in Normandy, and he focused on making improvements to the gardens which had required long negotiations with local authorities to allow a diversion of river water so he could have his own pond.

In his last decade, he painted little else but his famous and prized Water Lilies (or nympheas), which he called paysages d’eau (waterscapes), which became more and more abstract with the passage of time. He painted more than 250 of them, allowing him to accumulate considerable wealth and to cement his legacy as one of the most important painters in history.

Fun fact: one of the Water Lilies paintings sold at Sotheby’s this past May for $70 million.

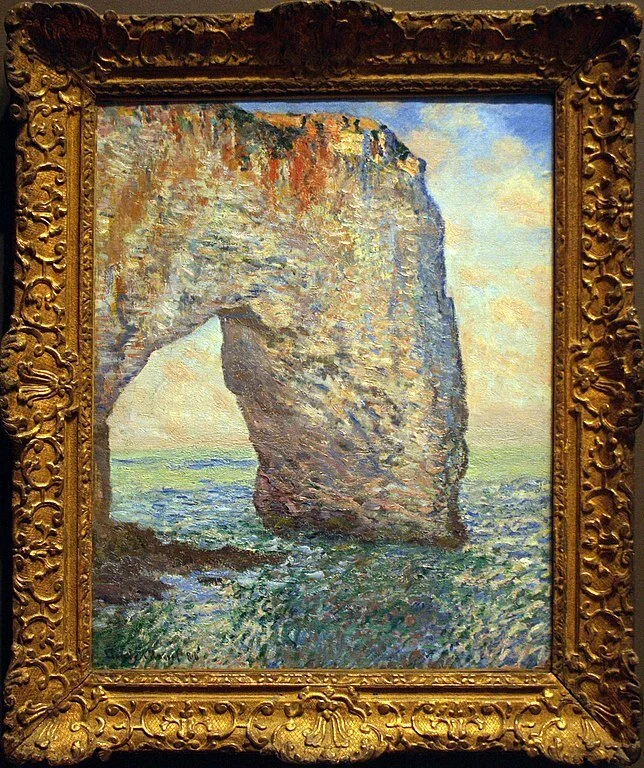

Claude Monet, The Manneporte near Étretat, 1886, oil on canvas.

Getting The Blue Mind

Wallace Nichols is a renowned marine biologist and author who for decades has been studying the phenomenon of water and the human brain. Here are some of his main findings, which are described with great detail in his book '“Blue Mind: The Surprising Science That Shows How Being Near, In, On, or Under Water Can Make You Happier, Healthier, More Connected, and Better at What You Do”:

1. When you put yourself at the edge of the water, your field of vision is simplified and so is your auditory spectrum.

2. When you get into the water, the hundreds of muscles that have been holding you in standing position no longer need to do that work, and the brain regions that were taking care of that get a break.

3. The default mode network is activated and you go into the “default mode,” which is a more contemplative, self-referential perspective. Your brain doesn’t have this complex auditory and visual input, so it goes to work on some other things. This is when you achieve a state that according to Nichols is called “Blue Mind.”

4. That mindset, that default mode, opens us up to a whole toolbox of cognitive, emotional, psychological, and social skills that are not always available to us in our Red Mind mode, where we’re rushing around, processing lots of visual information, taking in and filtering lots of sound.

The good news is that according to Nichols, you don’t have to be close to the ocean, a river or a pond. Getting inside of a bathtub full of water has a very similar effect on your brain. Sitting by a functioning urban fountain works well too.

While I hope you can be close to water this summer (or always, really) even the rhythmic sound of waves in meditation tracks can make your brain reap some of the benefits of getting into the Blue Mind. The app myNOISE is free and offers a bunch of different water sounds to choose from.

If you have any anecdotes regarding how water has helped you come up with better ideas, I’d love to hear from you!

Thank you for reading this far. Looking forward to hearing from you anytime.

There are no affiliate links in this email. Everything that I recommend is done freely.