Art In Conversation

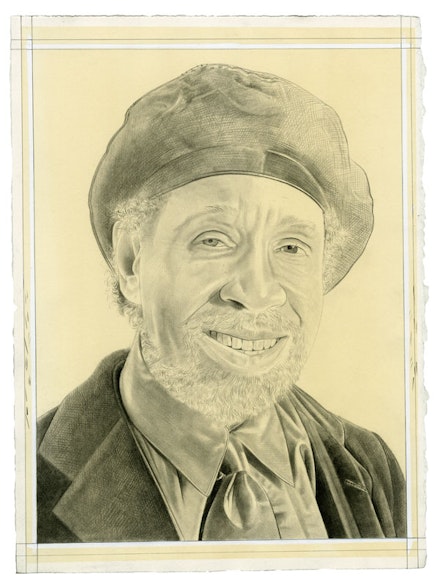

BARKLEY L. HENDRICKS with Laila Pedro

Since the 1960s, Barkley L. Hendricks has been creating powerful images of intense formal sophistication. Engaging and reworking conventions of portraiture, fashion, and iconography, Hendricks’s work reveals an intense visual focus and a concern with the tactile, technical, and chemical effects of of paint, pigment, and surface. On the occasion of his second solo exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery (March 17 – April 23, 2016), Hendricks spoke with Laila Pedro about creating illusions, photography as complementary practice, and learning to work with gold.

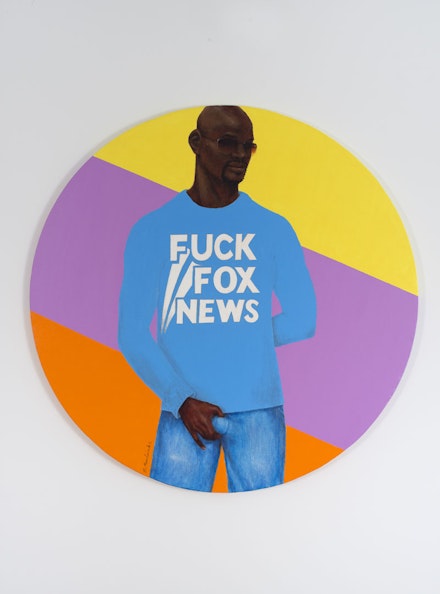

Laila Pedro (Rail): The paintings in the current show are graphically political—with text like “Fuck Fox News” prominently featured. In your early works from the ’60s and ’70s the politics seem more iconographic, emerging through relationships of subject, scale, and composition, rather than through words.

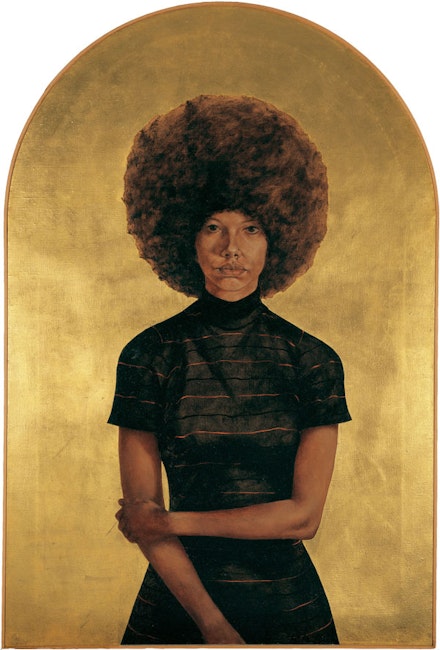

Barkley Hendricks: Let me correct the assumption that my early work was explicitly political. I was only political because, in the 1960s, America was fucked up and didn’t see what some artists or what black artists were doing. It was political in their minds. My paintings were about people that were part of my life. If they were political, it’s because they were a reflection of the culture we were drowning in. One example is Lawdy Mama (1969). The sitter in Lawdy Mama is my cousin, who had a beautiful ’fro. There are always reactions to that piece from people who thought they knew something about art, thinking it was Angela Davis, or someone like that. No. I did it because it was my cousin.

Rail: Lawdy Mama is an iconic work—literally. Formally, it recalls Byzantine icons. Was that a way of rendering sacred those close to you?

Hendricks: I did several paintings with arched tops. Three of them together were part of my “Basketball” series. I had one arch piece left, and it turned into Lawdy Mama. It was the first time I used gold leaf for the background. That was my first major gold-leaf painting. So it was an education.

Rail: An education in what sense?

Hendricks: I’ll give you a technical background in terms of what I experienced. First of all, I was working on a canvas. Usually gold leafing is done on a surface that is rather rigid or even hard; it’s done on panel. Many of the major icons were done on very hard surfaces to ensure that they could be burnished or made shiny—that they could be gone back into with tools that would give a kind of glow or reflective quality. I was using canvas, and canvas didn’t have that rigid back surface on which to use a burnisher. What came through was the texture of the canvas. And that was cool with me. I didn’t need to burnish it or make it shinier than what it was.

The second area that kicked my ass was the fact that I knew nothing about the whole process of leafing; I knew only what I read. When I did a study piece, it helped me deal with the larger one. I found that I had misrepresented the amount of time it would take and the material that I would need given the time. What I mean by that is that there are a number of different glues, or adherents. At the time I’d gotten a slow size, which meant you could put the adherent down and wait for a particular amount of time to get ready and then you’d lay the gold leaf down. I was actually working on that piece for almost ten hours straight. The lesson I learned was how to modify the time experience. It depended on if I used slow or fast size. That was an important lesson.

The third lesson was that gold is very finicky, very delicate. The slightest wind or heavy breath will send it fluttering all over the place. I had to close all the windows so there was no air circulating. I had started with my air conditioner on and a window open and I realized the slightest gust would crinkle it up so it wouldn’t work. So that was the next lesson I learned about working with gold leaf.

Rail: Your paintings sometimes recall candid photographs drawn from in-the-moment experiences.

Hendricks: I had a painting from when I was in the Army. I took a little camera and I shot some things. One of the pieces that I did was of a fellow recruit that I had a bit of fun with in terms of sarcasm with his image. He was a Private. And I did a painting with a Lieutenant’s bar on his helmet. I called the painting FTA (1968), which stands for “Fuck the Army.” When we were marching we’d chant that: “FTA all the way!”

Rail: Did being in the Army affect your work in other ways?

Hendricks: Made me want to stay the fuck away from the Army.

Rail: Did you continue working with photography after that?

Hendricks: Yes. Photography has always been an important adjunct. I went to Yale and took a class in American photography. I spent more time with the photographers at Yale than with the painters.

Rail: Why was that?

Hendricks: The painters weren’t figurative; most of them were abstract. They were pour painters. They were nice guys, but it wasn’t anything that interested me. The photographers offered a direction that I didn’t know a lot about, like working with the Zone system and the printing area of imagery and the variety of cameras. I learned a lot from them.

Rail: Speaking of pour painters and non-figurative painters, you were doing primarily portraiture at a time where most of the value and focus in the art world were on formalism and abstraction. What was your relationship with other painters, and with what was going on in painting around you?

Hendricks: I didn’t give a fuck what was going on. There’s nothing new out here. That’s what irritates me about this culture—it always wants to play some dumbass game. I didn’t care what was being done by other artists or what was happening around me. I was dealing with what I wanted to do. Period.

Rail: Can you tell me about the composition of the new works, in the current show at Jack Shainman Gallery?

Hendricks: I was actually thinking just yesterday about writing something about these images myself. Previously, as in my survey at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2008, most of the paintings leaned more to oil than acrylic. Now there’s an equal amount of acrylic—if not more, in some areas. I’ve been learning to manipulate and work with acrylic a bit more from a standpoint of drawing and image making, rather than the acrylic being a backdrop or the flat area of my pieces. This body of work relies on acrylic coming closer to the way I would have handled watercolor. I love watercolor a lot. Some parts of the paintings have a watercolor quality in terms of the drawing. I’m being more ambidextrous and am more able to marry the two in ways that I feel happy with, in terms of what I’ve learned over the years handling watercolor. Watercolor is a transparent medium, so it is about using that approach. And it’s a quicker drying medium so if I needed to make an area drier I just whip out my hair dryer and get my area dry so I can work on it quickly. There are some areas of detail where, now, it is a bit more logical to use an acrylic approach.

I have a series of paintings that I call my “Limited Palette” series. The one I’m working on currently is white on white. The way the watercolor approach works for me is that now I don’t have to use an impasto quality of paint layering: I can use more of a watercolor to get what I want. An interesting situation with my “Limited Palette” area is a work that was recently acquired by the Whitney Museum, called Steve (1976). It was a white-on-white piece that was oil, acrylic, and Magna. Magna was a paint that was used that was very workable, close to oil, but it dried faster. Being a synthetic resin material, it wasn’t supposed to yellow. Oil, being a paint that was ground with linseed oil or walnut oil, over the years would tend to yellow a bit more than acrylic and Magna. So I wanted to use the double-core Magna for the clothing area. It had gotten damaged with the previous owner and the Whitney acquired it and put their conservation team on it. I haven’t seen it since it’s been restored. There was recently an article in the New Yorker, [“The Custodians: How the Whitney is Transforming the Art of Museum Conservation” January 2016], about their conservation team.

Rail: That was an interesting article, because it elucidated how quickly and critically conservation practices are evolving. As someone who is a very sophisticated technician when it comes to paint, what was your experience working with the Whitney’s conservation team?

Hendricks: It was interesting: when they acquired it they invited me to visit the museum and meet with them and talk about it. As you say, I’m a technician. I like the area of the chemistry of paint. When I was in art school, for example, I did not miss materials and techniques class, because it was full of knowledge. I find I’m constantly dealing with certain areas of chemistry. I had a nice talk with them.

Rail: Speaking of school, you were a professor for how long? You taught at Connecticut College, my alma mater, until 2010.

Hendricks: I was at Connecticut College for thirty-nine years. Before then at Yale, and at the Philadelphia Department of Recreation, and in various visiting artist roles. So I’ve been a teacher for over forty years.

Rail: Does teaching inform your practice in a useful way, or is it purely a survival mechanism?

Hendricks: Both. It’s a hand-in-glove situation.

Rail: In the current show, there’s a very powerful signifier of our cultural moment: In the Crosshairs of the States [2016] depicts a figure wearing a hoodie, framed within crosshairs. To be Titled [2015] has that same figure, but fragmented, so that there are several diamond shapes that make up the painting. It evokes, through a visual distillation, “Hands up: Don’t shoot.”

Hendricks: It’s a current theme that is part of the culture now. I’m touching on what’s going on. Have you ever been thrown against a wall and frisked? It’s not something I’ve experienced every day, but I’ve been thrown against a wall and frisked. Philadelphia was like a Gestapo city. The police chief there when I left in 1970 was a man named Frank Rizzo. Anywhere you went in areas of color you had to address the police. You had to watch out for the police and you had to watch out for the thugs. In a way the police and the thugs were one and the same.

Rail: The works in this show reflect some of your long-time themes: black bodies, fashion, posing. Are they a series of work unto themselves? Or do you see them as part of a sequence or lineage with your earliest portraits?

Hendricks: Well, I’m still alive. [Laughter.] So it’s a continuum. I was reading something in the Times this morning about the Hollywood situation. I was always relating to fashion issues. I was thinking, “Damn; I should do some women and more fashion.” I’ve done that before. But I mean the formal, floor-length dress, and heels, and things like that. I’ve done some sketches, but I haven’t done anything recently that has dealt with glamour fashion. I have a few friends and associates who would pose for me, but I haven’t moved in that direction recently because of what has piqued my interest as of late. My photography approach is such that, at Connecticut College, for example, I would constantly have models in the drawing and painting classes and I could take a glamour approach where we’d work with a given clothing industry. The wedding industry, for example, is a billion-dollar enterprise. So I would have a model with wedding dresses. Or the Halloween approach, where I would have someone dressed up in all kinds of Halloween costumes.

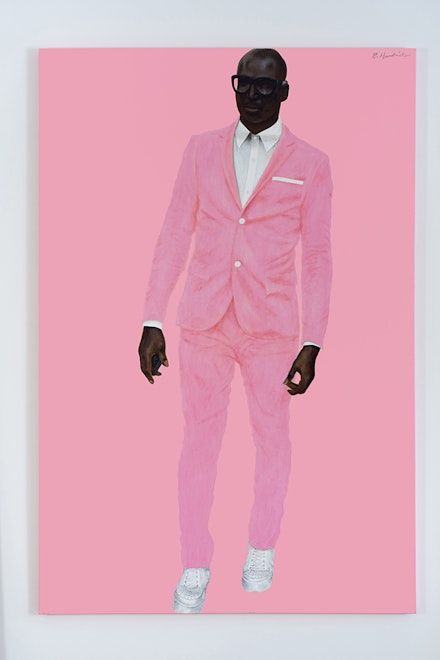

Rail: Maybe the most fashion-driven image in this show is the pink-on-pink Photo Bloke (2016).

Hendricks: That was a dude I met in London. He was actually doing some photography himself. His style was such that I had to approach him, and I took some images of him. That led to the pink-on-pink, although it’s not the first time that I’ve used pink as an area color in my work. Recently I’m using some of what’s happening in the culture again. I was just telling my wife, not long ago, that I did a series of three paintings of a young man, Michael. One of them was called Michael BPP (Black Panther Party) (1971). When I made that painting he was in the Black Panther Party. The next one was when he’d gotten out of the party. I called it New Michael (1971), and his attire was entirely different. Another piece was another image of him that didn’t reflect any of the attire that any of the Black Panthers were using. These were people that I knew. Michael BPP could be a part of the political shit. But I just knew him.

And the man with the pink suit was to me a logical connection to the area around him. I got the chance to mix up—I think—a beautiful pink with the acrylic. If you showed it under a black light it would get a little bit of a glow to it, because I used a paint that had a bit of ultraviolet in it, which gave a powerful pink.

Rail: Was he wearing that color, or did that emerge in the process?

Hendricks: No, he had on a color close to it. In that particular piece, I was working with how to make paint respond to what I wanted. I kind of laid the color down, and then used a way to take some color up so there’s a translucent element. There’s only two pieces where I’ve done jeans. You see a lot of people paint jeans. But no one paints jeans like me, with the consciousness of the fact that jeans are a material that is worn rather than painted. When I say “worn” I mean the way denim actually looks—you can see the fabric that has been worn down, especially now that they’re selling you material with gaping holes.

Rail: I’m wearing some right now.

[Laughter.]

Hendricks: I was actually busting a young woman’s chops the other day. I’d just come back from Manhattan and she had a pair of jeans with holes. And I said, “You know, it’s interesting. When I was growing up, if you went to school with jeans like that, they’d bust the shit out of you! They’d call you a poor motherfucker! You could not step out and be seen in any of today’s fashion.” Actually, I have a pair on right now with holes and paint on them—because I wipe my brushes on them.

Back to the approach to painting denim: The art of painting is not only about putting paint down. I like to use the texture of the canvas as a vehicle to get the illusion that I’m interested in. People have always connected me with a political situation. I’m more about illusion. When you look at one of my paintings, you’ll see that there are glasses, or a shirt that looks like wool. I want that to be something that resonates with you first, rather than you trying to be connected with the unfortunate situation people of color face. There’s a script that’s been written, whether we like it or not. We’re all a part of it. What needs to happen is for artists to get up and get out of that headlock scenario—out of that script that’s been written that you had no control over.

Contributor

Laila PedroLAILA PEDRO is a former Managing Editor of the Brooklyn Rail. She is a scholar and translator, and holds a PhD in French from the Graduate Center, CUNY.