Remembering Barkley L. Hendricks, Master of Black Postmodern Portraiture

The prescient painter—who died at the age of 72—documented the African American figure as a cultural, and commodified, phenomenon.

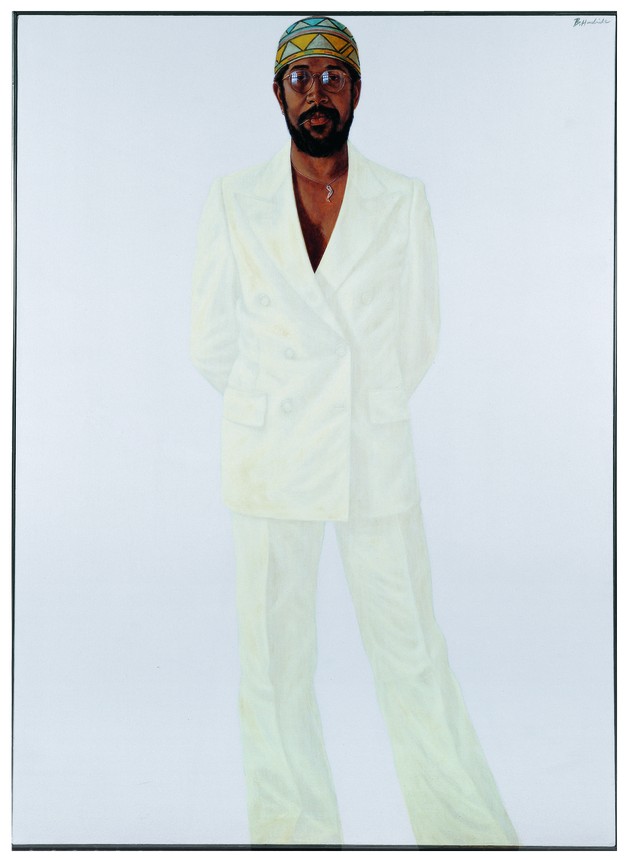

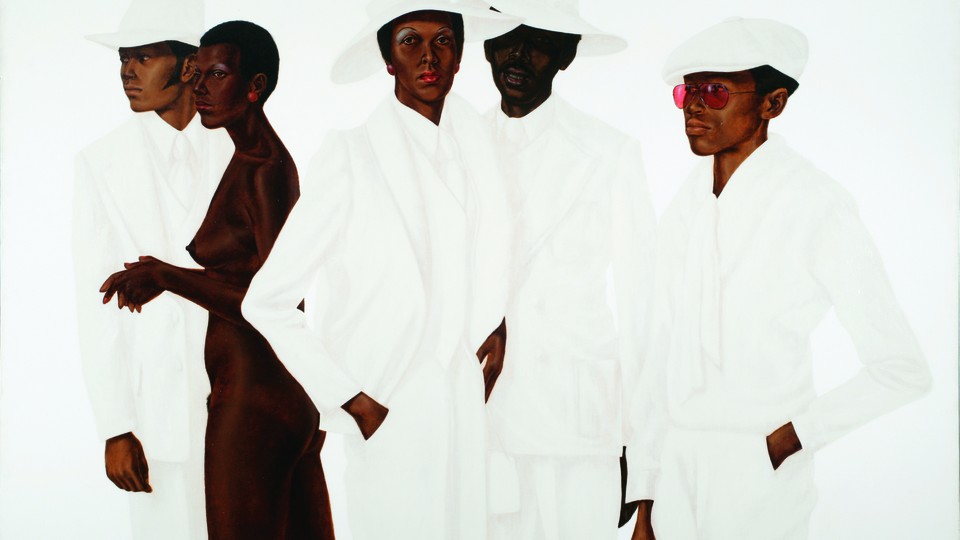

What’s Going On, one of the best-known portraits by Barkley L. Hendricks, arrived in 1974, three years after the Marvin Gaye album of the same name. At the time, Gaye’s record was well-regarded, but not yet universally recognized as a masterpiece of protest art. Hendricks saw in it something not far off, a moment when black protest music would come into its own as a commercial concern. His striking portrait acknowledged the record’s place in the commodification of black culture happening at a break-neck speed in the 1970s.

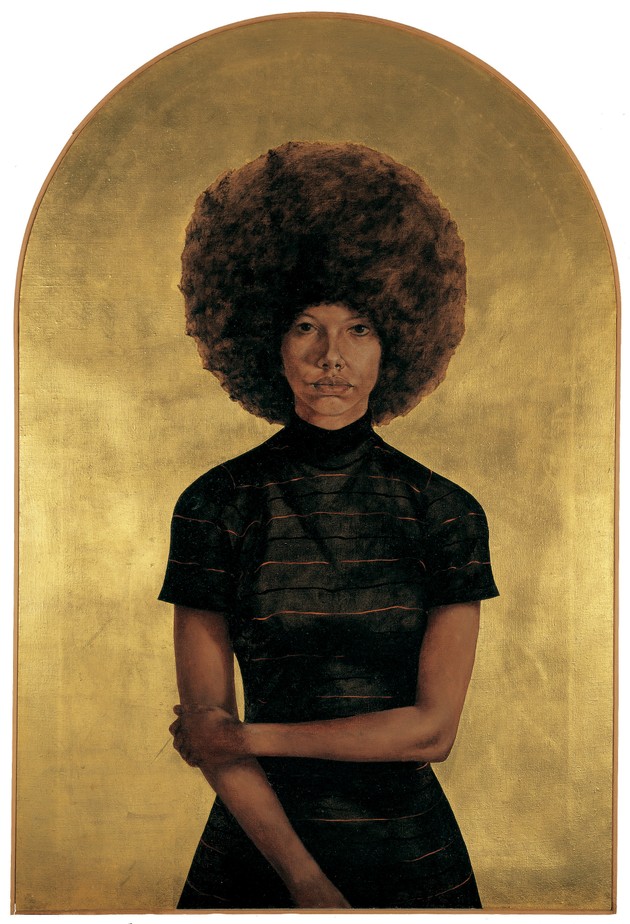

Hendricks, one of the finest figure painters of his generation, died on Tuesday at 72. Large in scale, his paintings combined the tonality of Rembrandt with the sensibility of Andy Warhol. His stylized portraits—realist African American figures set against abstract backgrounds—starred friends and neighbors from his life, posed for timelessness. His broader project was to document the black image as a phenomenon, as it manifested in fashion, billboards, magazines, and movies.

Along with Philip Pearlstein and David Hockney, Hendricks stands out as a pillar of postmodern portraiture. But he was never a well-known artist. While he is widely cited as a major influence among contemporary black artists today, Hendricks’s work is under-represented in American museum collections. That owes in part to his black subject matter, but also to interests that kept him away from painting for almost 20 years.

He has since emerged as an overlooked but critical artist who touched on Pop Art and historical painting. In a 2009 essay for Artforum, Huey Copeland, an art historian at Northwestern University, wrote that Hendricks’s paintings “illuminate the crisis of blackness within representation—a crisis everywhere shaped by an engagement with and an opposition to those persistent forms of reification, high and low, that transform liberatory self-fashioning into co-opted cliché.”

Copeland’s point about art bridging high and low sources of imagery could easily describe the work of Kehinde Wiley, one of the biggest names in contemporary art today. Wiley’s paintings of popular black figures (LL Cool J, Ice-T) in anachronistic, historical modes (Renaissance, Rococo) are forever indebted to Hendricks. The late artist’s influence is also evident in the work of Jeff Sonhouse, Mickalene Thomas, Amy Sherald, Rashid Johnson, and others—to say nothing of the scores of painters Hendricks taught at Connecticut College, where he joined the faculty in 1972. (He received both his degrees in art from Yale University.)

Hendricks challenged the strictures of the art world in sly and overt ways. In 1977, he painted a life-sized nude of himself, Brilliantly Endowed (Self-Portrait), so named after a line the art critic Hilton Kramer used to describe his style. Life-sized portraits of everyday black folks were hardly the way of the fine-art world in the 1960s, making him a radical; portraiture in general took a back seat in the 1970s, making him retrograde. His work could be dramatic—like his so-called limited-palette paintings, including What’s Going On, with its subjects’ crisp, white clothing blending into the background—but in the knowing way of a Blaxploitation movie poster.

In 2008, the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University organized a retrospective of Hendricks’s work that traveled to Harlem’s Studio Museum as well as to museums in Santa Monica, Houston, and Philadelphia (where Hendricks was born in 1945). That show, “Birth of the Cool,” curated by Trevor Schoonmaker, was the first to re-think Hendricks’s role in portraiture, at a time when interest in his work was at an ebb. (He stopped painting from 1984 to 2002, in part to focus on his photography of jazz musicians.) Recently, Hendricks’s work has gone up at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and at the Studio Museum; his paintings will also be at the center of the upcoming Tate Modern exhibit, “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power.”

In that show, Hendricks’s work may serve as something of a counterpoint. He never painted black people in protest or in crisis. Ideas about black nationalisms surfaced in his work as they were reflected in the world of images. He borrowed endlessly from the commercialization of black culture—a Pop Art way of turning the white gaze back in on itself. The artists who have followed in his footsteps are sometimes described as “post-black.” Hendricks may have beaten them to that.