Intro

The lyrics from the Bob Dylan song All Along the Watchtower — made famous by Jimi Hendrix — echoed through my brain as I sat motionless and breathing slowly in between two other divers in a small, cramped, claustrophobic, dark, and completely silted out space deep within the IJN Sata wreck.

“There must be some kind of way outta here

Said the joker to the thief

There’s too much confusion

I can’t get no relief”

Bob Dylan

This was no joke and I would be a thief if I cheated death and somehow took a breath of fresh air again.

The rebreather computers on our wrists and the blinking lights on the heads-up display on one unit were the only light. The computer was barely readable in the heavy silt — even when just an inch from my mask. Time ticked away and deco kept adding up….

Background

Before I get into the details and analysis of this accident, let me just say that all four divers involved are experienced rebreather divers. This was not a “rookie mistake.” Any one of us should have seen the warning signs and made different decisions. This is NOT the fault of any one diver. It is the result of complacency and probably some bravado of the team — including myself.

This is about my experience during the incident and doesn’t reflect what other divers felt or experienced. Everybody experiences events like this differently.

I have publicly posted in other forums about the importance of analyzing accidents in scuba diving similar to the way other sports do — for example, the excellent Accidents in North American Climbing by the American Alpine Club. This post will provide details of the incident, how we survived, and lessons learned both good and bad.

The day after the incident, I wrote down 2-3 pages of notes in my notebook in order to preserve them. Two of the other divers reviewed the notes and provided their perspective and more details (not all four of us were together the entire dive). The other three divers have reviewed and provided feedback on this post. It is my experience and how I felt during the events and it doesn’t necessarily reflect how they felt during the incident or after.

In order to shield the other divers, I have not named them. Instead, I will use the following

- Diver 1 – A local Palau diver with a lot of experience diving wrecks, including the IJN Sata

- Diver 2 – A world renowned wreck and rebreather diver with multiple thousands of wreck dives completed

- Diver 3 – John Entwistle – Has conducted multiple hundreds of hours on rebreathers on wrecks

- Diver 4 – Me

All four divers were on rebreathers from 3 different manufacturers.

The Dive Plan

The IJN Sata is the “sister ship” of the IJN Iro.

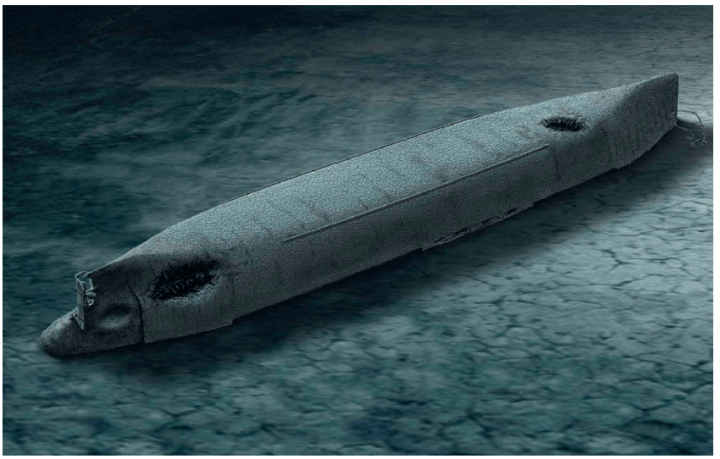

Both ships were Japanese oilers that sank in 1944 during Operation Desecrate One and only lay a half-mile apart in Malakal Harbor. However, there is one key difference — the IJN Iro sits upright while the IJN Sata is completely upside down. Below is an illustration of the IJN Sata from Rod Macdonald’s excellent book Dive Palau : The Shipwrecks.

On this dive, there were a total of eight divers along with a couple safety divers. Before starting the dive, the teams all agreed on the dive plans detailed below and a maximum runtime of 2 hours (for non-divers : the “runtime” is the time from getting into the water to exiting including all necessary decompression stops).

Two of the divers went to penetrate into the engine room at the stern that is accessible through the hole created by a torpedo hit (obvious in above illustration).

The six remaining divers planned to start at the downline which was placed at the large hole near the bow caused by a 2000lb delayed-fused bomb going off directly underneath her (also obvious in the above illustration). We planned to swim to the bow and take some wide-angle pictures and then separate into a team of two and a team of four.

The team of four that I was in were going to penetrate the wreck near the port side of the forecastle (entrance not obvious in the above illustration) and follow a one-way route (this is important) that Diver 1 had conducted many times in the past; however, it had been quite some time since he had last done it.

The Dive – Setting the Stage

As planned, we went down the descent line to the bomb hole, stored our Nitrox 50 bailout tanks and clipped clothes-pins onto the line with our names (useful to indicate who is still on the wreck and who has started their ascent) and our team of six made our way to the bow of the ship while the other two divers went to the stern.

When we got to the bow, three of us started working on natural light, wide-angle photos. The conditions were “okay” but not “great” for that type of photography.

At this point, we all went down to the opening on the port side of the ship near the rear portion of the forecastle. In the picture below, I believe that the thing sticking up is a lifeboat davit that got crushed and turned upward as the ship hit the bottom.

The Dive – Entering the Wreck

Once again, it is illustrative to use one of Rod’s excellent diagrams to show approximately where we are. In this case, I’m going to use the IJN Iro but remember that this is the IJN Sata so it is upside down and reversed.

At this point, Diver #1 entered the wreck since he knew the route. There was a hole near the stern portion of the forecastle on the port side that we entered through. He was followed by Diver #2, then Diver #3 and then me (Diver #4). The photo below shows Divers #2 and #3 waiting to enter and I’m taking the photo from above.

I will also introduce three points inside the wreck to make things easier to describe.

Remember that our plan was to have a different entry and exit point on the wreck. I will use “Point A” is the entry point, “Point B” is the planned exit point, and “Point C” is in between.

One of the reasons we didn’t plan on running a line is that our entry and exit points were different. I had not seen the interior, but at this point, alarm bells should have at least started to ring. Notice how much silt is bellowing out of the wreck after a single, expert diver has entered it.

It is also useful to include a diagram that shows the profile of the dive annotated with some specific events and their elapsed timestamps. I will refer to the points in the description of the dive below.

T1 – 16 minutes

At about “T1 – 16 minutes” into the dive, you can see in my profile where I start to ascend into the wreck, then descend and ascend and descend again. This was part of the route we were following and we were going into and out of spaces in the forecastle area. As mentioned previously, the wrecks in Palau typically have a LOT of silt — especially wrecks and their interiors that are not dived very often.

It is also important to remember that this wreck is upside down and the weight of the hull has crushed the empty spaces where we are traversing. There is a jumble of metal with sharp objects and no obvious path. I’ve included below a few of the pictures I took as we were making our initial penetration.

The last photo I took on the dive is on the bottom right. My dive computer and camera weren’t time-synced, but it was about 20-23 minutes into the dive (or about 7 minutes after I first entered the wreck).

The Dive – Stuck

During complex penetration dives in wrecks, it is normal for congestion to occur as the divers try to make their way past obstacles and restrictions.

T2 – 33 minutes

At about “T2 – 33 minutes” we were at a point where we had stopped and I was waiting. The lead diver (Diver #1) came back to us and indicated that the route to Exit Point B had been blocked. Many of the old WW II wrecks are collapsing after almost 80 years under water and the IJN Sata is no exception — this is accentuated by the fact that it is upside down.

This was the first time I thought “we are in trouble” but remained calm.

We all gathered at “Point C” (in between Entrance Point A and the original Exit Point B) to figure out a plan.

One of the “commandments” of wreck and cave diving is “Don’t get lost, and when lost, don’t get ‘loster.” I think I first heard that from the famous wreck diver, John Chatterton.

T3 – 43 minutes

After spending some time figuring a plan, we tied off my reel with 200 feet of line and Diver #1 led the way in our first attempt to find our way back to Point A (the original entry point). In succession, all four of us followed the line being laid by Diver #1 — which only exacerbated the situation by stirring up more silt and slowing us down.

At one point during our exit attempt, Diver #1 came back and said that it wasn’t the correct route and that we should go back to Point C where we had initially gathered. The four of us made our way back along the line to known Point C.

T4 – 60 minutes

At this point, it is an hour into the dive and we are back at our tie-off somewhere in the wreck at PointC. I was definitely getting worried but the four of us remained calm and started evaluating and discussing our alternatives. One fact that we all knew: we were on rebreathers and we had time to figure out a plan.

The Dive – The Wait

Tom Petty has a famous song with the line “The waiting is the hardest part” and that certainly described the next 90 minutes.

When you dive a rebreather, you can “kind of” talk to each other since you are talking into an air pocket in the diving loop. We all “talked” about alternatives and decided that since Diver #1 knew the wreck the best (and also the sister ship IJN Iro which has a similar layout), he would attempt to find an alternative exit to Point A OR an alternative way to get to the exit at Point B.

I believe he first went to find another exit to Point B and was gone for about 20 minutes or so. When he returned, he decided to try to find another way back to our initial entry at Point A. He was gone for some time and I was definitely starting to worry. I think at one point I said to Diver #2, “we are fucked.” But, the three of us stayed together at Point C and remained calm.

Waiting for somebody else to help get you out of a situation is really hard.

T5 – ~ 110 min

After some period of time, Diver #1 came back from his attempt to find the initial entry point (Point A) and I remember him talking to Diver #2 and writing on his underwater slate something along the lines of “found the initial entry but it is now blocked!” Apparently when trying to make his way back to the group, something inside the wreck collapsed (partially on Diver #1) and that it obstructed the exit.

We were probably about 100-110 minutes into the dive at this point (40-50 minutes of waiting at Point C) and I start thinking that our only real hope is to be rescued. I knew that our expected runtime was about to be exceeded and that meant that people would likely come looking for us. I also knew that two of the eight divers are world renowned cave divers with experience helping with rescue situations.

However, given what I knew about the wreck, I thought the chances of anybody finding us was pretty slim. It wasn’t zero, but it wasn’t looking great.

We all checked in with each other on how we were doing and on our critical limiting factors – how much oxygen did we have in our rebreathers and how much time did we have left in our “scrubbers” that remove carbon dioxide. I had plenty of oxygen to last at least a few hours but I started to worry about my scrubber. The details of why I was worried will require a bit of of a detour to explain how scrubbers work. Casual readers might want to skip ahead to the next section.

Sidebar : Scrubbers and the rEvo Rebreather system

Every rebreather has a scrubber that contains some absorbent that looks like kitty litter. Every rebreather except for two (rEvo and KISS) that I know of has one large canister to hold this material. A typical canister will hold about 5-7 pounds of scrubber material which will last anywhere from 3-4 hours to 6-7 hours or more depending upon conditions (water temperature, breathing rate, etc).

The rEvo has two smaller canisters that get “rotated” under normal operation. This should typically result in more efficient usage of scrubber. Each canister has about 3.3 pounds of material and typical scenario would involve removing the “top” canister at the end of the day and replacing it with the partially used “bottom” canister and then installing a brand new canister in the bottom. I won’t go into the details of why this can sometimes be more efficient. However, I did this operation the night before our dive so I effectively had a partially used top scrubber and a new bottom scrubber.

The rEvo also has an option to monitor the temperature of each scrubber at multiple points to estimate the duration of the scrubber at any point during the dive. I don’t rely on this too much but use it more like a fuel gage — is the tank full, half-empty, or running on empty? This would have been VERY useful to have on this dive given all the circumstances. However, as timing would have it, the 9V battery that powers this system had run out of juice during this specific dive and so I was flying somewhat blind.

The Dive – The Wait Part 2

At this point we were all concerned and Diver #1 again went to look for an exit path to get out to our initial entry Point A. We had agreed that he should “take no more than 20 minutes – 10 minutes out and 10 minutes back” since no time limit had been set on the first few attempts.

After a little while, the three of us at Point C started to hear a loud banging of three “thumps” in a row. At this point we were either at or a bit past our 120 minute agreed upon runtime. Diver #2 would bang back three times every time we heard the signal. My hopes started to grow that at least we knew they were actively looking for us (these would soon be dashed).

This continued for a good 15-20 minutes. I knew that there was likely no way for any rescuer to follow a deep banging to find our specific spot (especially in such a jumbled mess), but it could probably at least get them close. During this time, I learned later that Diver #1 had made three additional attempts to find an exit and had run the line the full 200 feet out but could not locate any suitable way out.

After a while longer waiting at Point C, the three of us started hearing a different kind and pattern of banging and we were getting very confused. It at least gave us something to think about other than being forever entombed in the wreck. When we first heard the other banging, I remember looking at Diver #2 with a quizzical look in my face and he looked back with a similar look. But, we continued to bang back in a pattern that repeated what we heard.

The Dive – Relocating Diver #1

T6 – 150 minutes

After the banging stopped for a while, the three of us decided that we couldn’t stay at Point C any longer and that we needed to go find Diver #1. He had exceeded his planned 20 minute attempt by a lot and we thought maybe he was trapped or having problems.

Therefore, we slowly all made our way along the line making very sure to NEVER lose the line. In cave training, you are taught to circle your thumb and forefinger around the line in the “okay” symbol and NEVER let go. If you need to go around a post or other obstruction, you find the line with your other hand before you let go.

I cannot over-emphasize enough how bad the visibility was. It was literally almost zero and the only light we had was our dive lights so if you lost the line, you are in even bigger trouble. In this type of silt, it takes DAYS to settle down and we didn’t have that long.

I noticed during this process of following the line and finding Diver #1 that we were gradually decreasing our depth (getting shallower) which meant we must be going into the hull area of the ship (remember that it is upside down).

T7 – 158 minutes

As we rose up into the hull, the visibility improved since it was a large open space and the silt was lower in the wreck. You can see in the dive profile diagram that the depth was much shallower than the rest of the dive. We were now at about 85 feet which meant that our decompression obligation would be increasing but at a slower rate.

What I saw next made my heart sink: Diver #1 was banging his bailout tank against the hull.

I instantly thought “uh oh – that wasn’t the rescue party trying to find us, that was Diver #1 trying to alert the rescue party.”

At this point, I turned to my friend, Diver #3 and said something along the lines of “we are really fucked.” I also started to think about the pain I would cause my wife and my family if I didn’t get out. I didn’t panic and was completely rational, but the situation was not looking great.

As my decompression obligation kept increasing, I remember thinking that I would do whatever amount of decompression was required if I could just get out of the wreck.

We weren’t ready to give up and as a team we started to formulate a new plan.

We would leave in place the primary line that we had been using that now ran from Point C up into the cargo hold. Diver #3 and I would stay at the end of the line and continue banging a tank to signal the others. Divers #1 and #2 would each run a spool of line off of the “main” line in an attempt to find an exit. We were all determined to get outside the wreck.

The Rescue

Things were definitely starting to look grim. Diver #1 had gone off again in search of an exit and Diver #2 was preparing to do the same.

T8 – 170 minutes

After some time, I was looking around and noticed a light coming towards me. The shape of the light was different than any of the others in our group and I wondered if maybe somebody had switched lights or maybe one of their lights had failed. It was then that I saw the distinct orange drysuit of Antti Apunen. He was the one diver I had been pinning my hopes upon – Antti is an expert cave/wreck diver and had done several other rescues in the past.

He had his own reel with his own line with him and I instantly knew that we would somehow be able to get out.

He asked if I was okay to which I replied that I was. He showed me his line to differentiate it from the line that we had put in place. He indicated that I should follow his line (and not ours) to the exit. I made sure the others knew that he was there and then started down his line to the exit. This descent can be seen in the diagram from T8 to T9.

Getting Out

The exit path was a bit complicated but not too bad.

Antti had laid a good line to follow and I do remember descending a lot and weaving my way amongst jagged metal beams and other obstructions but I was happy to know that one way or another I would get out. I was VERY careful not to let go of that line at any point even when following it around the obstructions.

T9 – 175 minutes

At that point I came to a very, very small opening between a piece of metal and what appeared to be mounds of silt. I thought to myself “why didn’t he run the line OVER the beam and not under it?” It turns out that it wasn’t a beam but was instead a solid piece of metal with no way to go “over” it and that I would have to squeeze under it.

On my first attempt, there was one of the other divers on the other side that grabbed my hand and said “it will be okay, we will get you out.” After several more attempts to get under the restriction, I was getting exasperated. I rested fora minute or so and then made another attempt. At this point, I realized that (1) I was going to stir up a ton of silt no matter what I did and (2) I would need to put a few things through the restriction before I went through.

I proceeded to unclip the rear of my bailout tank and push it through ahead of me along with my camera. I then literally started to bury myself into the silt piles and wiggle my way under the beam. I got stuck and the diver on the other side was trying to pull me through. He was shoving me down into the silt and I finally was able to move around enough and wiggle enough to get through.

To this day, I still am amazed that Antti chose that path to enter the wreck given how hard it was to get out.

The Exit and Decompression

After I got through the restriction, I wasn’t sure how far along the exit path I was. I kept following the line and could see a “green haze” ahead of me which must mean the exit.

T10 – 183 minutes

At this point, we had been underwater for three hours and had spent almost all of that time inside the wreck and had an increasing decompression obligation but I was happy to be on the path to the exit. After I saw the green-ish haze, I continued to follow the line until it came to an end but it was so silty that I couldn’t really figure out where I was but knew that if I could see something without artificial light that I must be at the exit.

I felt around and finally found the edge of the ship and started to slowly make my way up the side. I was met by one of the six divers and he asked if I was okay to which I replied that I was. He indicated that we should join up and he would lead me up to the downline (in case I was dis-oriented). I knew exactly where I was.

I grabbed my clothespin from the line and started my ascent and decompression. One of the things wreck and cave divers sometimes do is that they leave a “marker” or “cookie” on the downline or at the entrance and pick it up when they leave. This allows other divers to know who has come out and who is still in the wreck or cave.

This was my symbol that I had survived and it is still on my workbench today.

My decompression obligation was about 80-85 minutes which I was happy to serve.

We stayed on the downline until all four divers had completed their deco obligation and we all did some extra time to help prevent any decompression sickness from occurring after a stressful dive.

I’ve done much longer decompression schedules (about 2.5 hours) but I’ve never had a longer dive (5 hours, 21 minutes). If the wreck had been deeper, our decompression obligation would have been significantly higher and we likely would have had to switch to open circuit tanks to complete it.

The Rescue (from the Surface Team perspective)

After the dive, I spent some time talking with the crew of the Palau Siren along with the other four divers that helped us get out. Here are some of the things I learned during those discussions:

- After our 120 minute runtime expired and they didn’t see us, they knew there was a problem and immediately started working on a plan.

- They alerted the local authorities who offered to help to which they said “sorry, we are grateful, but the divers you would send don’t have the skills or training to conduct this type of rescue.”

- The divers that came back into the water to help us only had a surface interval of about 15 minutes which is far from ideal and could have resulted in a higher likelihood of them getting the bends but they did it anyway.

- They weren’t sure where in the wreck we were. Two of the divers had seen us enter but they conducted their dive and didn’t know if we exited and had gone into another location.

- Diver #1 banging his tank was very helpful. It let the others know that (a) at least one person was alive and (b) that we were still in the same general area of the ship we entered

- The “lead” rescue diver (Antti), when he got to the entrance, immediately tied off a line and started his search and entered the wreck without any hesitation — even though he knew it was dangerous and was very silted out. We weren’t about to give up trying to get out, but I’m not sure we would have made it without him finding us and running a line from the outside. I told him and continue to believe that I owe my life to him and will be in his debt for the rest of my life. He smiled graciously and just said that he was happy he found us all alive.

- Antti still isn’t sure why he took the path he took. He said he could have gone “left” or “right” once inside the hole to try to find us and just picked “right.” After “diving by braille” due to the limited visibility, he kept poking around and finally found our “main” line that he had put down and then quickly tied into it and found Diver #1 followed by me and then Diver #2 and Diver #3.

- Antti, who has conducted quite a few rescues, rated the seriousness of the rescue “about 8” on a scale of 1 to 10 and then later said “9 or 10” after seeing the initial photos I took inside the wreck.

Lessons Learned

We debriefed after the dive and discussed things that we felt we did right and wrong and the lessons we learned. These are my interpretations of those but I believe they are useful. I take full responsibility for my decisions and blame no-one — other than myself — for getting trapped.

What We Did Wrong

As crazy as it seems, the list isn’t long but it is critical.

- We didn’t put in a line when entering the wreck. There are no excuses on this, but there are some mitigating reasons:

- It was planned to be a “one-way” traverse

- Diver #1 had conducted this dive many times in the past

- Four people inside that wreck on that route is too many

- I’m not sure I should have been in that specific wreck. The wrecks in Palau are silt factories and without perfect trim and finning, you will silt out spaces easily. I am far from perfect. In many cases, that is okay because the penetration isn’t long or it is an obvious route. Neither is true in the IJN Sata.

- We didn’t properly evaluate the risks of doing a complex penetration on an upside down and collapsing wreck from WW II

- We didn’t verify the exit on a one-way route

- This is “standard” for cave diving. If you are doing a one-way traverse, you should verify the exit before you start

- This somewhat implies that the exit “restriction” is closer to the actual exit than the midpoint of the dive. In our case, I believe our initial block was about the middle of the path so the value is somewhat diminished. After all, if the key restriction is midpoint, then the only way to verify the exit is to do that whole dive and the entry side and exit side are arbitrary.

- Going on a “Trust Me” dive

- 3 of the 4 divers had never been in this wreck and didn’t know the conditions

- As mentioned earlier, we are all experienced divers and when we didn’t feel comfortable, we should have either called the dive or put in a line. “Trust me” dives are okay, but if it doesn’t feel right, then…

What We Did Right

We made some big mistakes, but there are a few things we did right:

- Before entering the water, we set an expectation with the surface team and other divers on our expected runtime and our dive plan

- When we realized that our initial exit path was blocked and that we were “lost,” we put in a line and none of us ever left it

- We stuck together (if you concede that it was smart to send one diver on a line to search for an exit instead of 4)

- We communicated and didn’t panic or blame and instead searched for solutions

- Banging the tank helped alert the others that we were alive and inside the wreck

- We didn’t quit

- There are too many stories of divers who spent their last minutes of life writing notes to their loved ones instead of continuing to try to get out of the situation. More than one of us thought about those stories during our long wait at Point C.

- We were using rebreathers. I am sure we would have died had we been on open circuit “traditional” scuba

- At a SAC rate of 0.5 cubic feet per minute (this would be considered a good diver’s rate), at 100 feet of average depth, we would have needed 366 cubic feet of gas to make it to the 183 minute mark where I exited the wreck and divers could have provided extra gas.

- An average set of double AL80 tanks has about 150 cubic feet of gas.

Closing Remarks

Looking back, I believe that over the past couple of years of diving, I had become complacent and probably over-confident. I will continue to dive but will avoid penetrating complex routes on upside down wrecks and will more explicitly think about risks and ways to mitigate them. I am eternally grateful to the team above the water and in the water that came back and rescued us.

I will close with two quotes.

The first one I saw recently and I believe it sums things up about this experience. No matter how well I try to describe it in words, it is hard to understand the feelings, hopes, fears, and the highs & lows that you feel when you experience something like this.

These things must be experienced to be understood

Edward R. Murrow

The second is one of my favorite quotes and I think it about it often during my dives.

Life is either a daring adventure or nothing

Hellen Keller

Stay Safe.

Wow… it’s crazy how reading something like this can raise MY blood pressure. Glad you all made it out safely.

I am almost speechless…unbelievable and so very glad you got out safely!!! This reads like a story of “amazing adventure” vs. our friend’s diving experience. Wow!

Mark Smith … speechless? Naw, never! It must really be crazy then! 🙂

Brett, glad you made it. Calm in Crisis is the key to success!

Thanks, Barry!

What a story Brett. I did read it in one breath (no pun intended). Glad you all made it out in one piece. Also encouraging to see you will still continue your passion.. Diving. All the best.

Thanks, Arjan. Yes, it was definitely a crazy story.

Thanks, Arjan. I hope you are doing well.

Brett, I really enjoyed the way you dissected the near miss and what we can all learn from it. I am very grateful you each made it back to the surface. The way you described the timeline, it felt like being there without the anxiety you all experience. Fabulous read, especially with the all safe ending.

Thanks for reading and for the feedback, Chris.

Thanks, Chris!

Thank you for sharing your story. As a community, we can only learn from our collective mistakes if people are actually willing to share them but it is not easy and takes courage. Glad you made it out alive. Gripping read, too!

Thanks for reading and the feedback.

Thank you for sharing this!

Thanks for reading and commenting, Stuart.

Thank you so much for sharing, we all need reminders to remember what we do is dangerous and not to become complacent. Glad you all made it out safe!!

Thanks, Mike. Dive safe!

I get the things you did wrong and the things you did right sections. Other than recognizing you’ve become complacent over time (normalization of deviance), what do you plan to do differently (better?) in the future, both in our local So Cal waters and elsewhere? Both in terms of safety margins and general dive practice? “…avoid penetrating complex routes on upside down wrecks” is kind of like saying “I won’t do stupid things”, but we’re all human and do stupid things which are obvious in retrospect but not necessarily at the time we do them. I’d love to hear how you think this will change your diving.

I can’t imagine the thoughts going through your head throughout the ordeal! Great writeup, and it reminds me of parts of Shadow Divers and The Last Dive

IMHO, the real key is not relying on others to make decisions.

Thanks for sharing. I’m still only a recreational diver but I think we can all learn something from stories like this. Particularly the humility it takes to reflect on the mistakes and to share them so publicly.

Thanks for reading and for the feedback, Ross.

This story made the hair on the back of my neck stand up. I can’t image for a second what must have been going through your head, or the mental toughness required to stay calm and logical in such a dire situation. Thanks for sharing there are some lessons here that everyone can learn from.

Thanks for the feedback, Marc.

This is the best, most accurate, most useful and most honest post dive analysis I have ever read. Thank you for this. It is a valuable lesson to all of us.

Raphael – Thank you very much for reading and for your comments. It isn’t easy publicly admitting when you screw up badly, but I am hopefully that it will help others. 🙂

Thank you Brett for sharing this, and your honesty; have you thought of sharing it with Gareth Lock over at ‘The Human Diver’, for his thought on the human factors involved?

Thanks for reading and your comments. Gareth was in the front row for the DEMA presentation. 🙂

Thanks for being open and sharing the mistakes made. Learning too often comes from fatalities and lessons learned are too frequently confirmed the same way. “Trust me” dives and traverses without confirming the exit are two basic rules I hope I never forget or choose to break. Your willingness to share this is critical and may well save lives.

Thanks for the feedback!

Brett! I feel like I held my breath through this entire story! So glad everyone made it out safely.

Paige – Thanks for reading and for the thoughts!

Very informative and useful for those becoming involved in wreck diving. I’d also be interested to know what the surface team might do differently should a similar incident occur. You mentioned that their surface time was only 15 minutes….

Thanks for reading and for the feedback. I wasn’t on the surface (obviously) but from my perspective, they did everything right. We didn’t have time for them to do a “real” surface interval. They chose to get back in the water 15 minutes after their own 2+ hour dive so that they could start a rescue plan because they knew our time would be limited.